The Death Penalty

Analyzing the deterrent effect of capital punishment in the United States: a systems perspective

David A. Burton

Cary, NC USA

Wed, June 10, 2015; updated August 26, 2015

I used to oppose the death penalty, long ago, but after I studied the statistics I changed my mind, because it became clear that capital punishment deters a lot of murders.

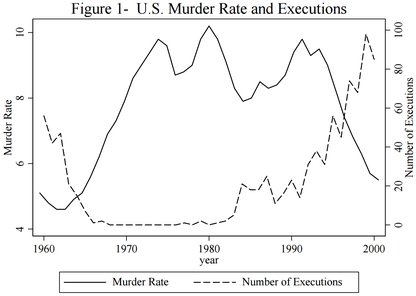

Here in the USA, when we phased out capital punishment in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the murder rate doubled. When we reinstated capital punishment on a small scale, the murder rate fell by 22.5%, even though the overall violent crime rate hardly budged.

Now, ask yourself, what would bring down the rate of capital crimes, without affecting the rate of other violent crimes? What would deter only capital crimes?

Isn't the answer to that obvious?

BTW, I've not done a systematic state-by-state survey, but I noticed the same effect in New York State. When New York reinstated capital punishment, their murder rate fell dramatically, even though they hadn't actually executed anyone. Just the threat of capital punishment was apparently sufficient to help lower the murder rate (though the Bratton/Giuliani community policing reforms in NYC also surely helped a lot).

That's why I changed positions, from opposing capital punishment to supporting it.

In the 1960s and early 1970s all violent crime rates rose. But the thing which was convincing to me is that when executions were resumed for the crime of murder, the murder rate fell considerably, even though the overall violent crime rate didn't budge.

I didn't get that from some article, by some author who might have cherry-picked his stats to spin the result. I discovered it by looking up the statistics myself, in almanacs, after hearing some expert on TV claim that there was no statistical evidence that executions deter murder. (Remember almanacs?)

When I heard that guy say that, I wondered: could that be true? No deterrence at all? So, being a suspicious sort, I went to the library, and found out, on my own.

What I found was that what the guy on TV said wasn't even close to true. It was clearly, flagrantly, provably false.

Shifting topics slightly... Incarceration with no chance of parole, but no threat of a death penalty, is also problematic, because it puts other inmates at risk. A murderer incarcerated for life, with no chance of parole, but no risk of execution, is a very dangerous person. He has nothing to lose. What is his disincentive to shank other inmates? What can they do to him, after all?

If someone you loved was in prison for some crime that carried a relatively short sentence, would you want people like that in there with him?

Here are some statistics (thanks, google):

Murder rates (per 100,000):

http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/

Crime rates (raw numbers):

http://www.disastercenter.com/

Executions:

http://tinyurl.com/USStatAbstrExecut

In the 1950s, there were 717 civilian executions in the USA. In the 1960s executions tapered off and then ended, with a total of only 191, all of them before 1968. In the 1970s, until 1979, there was only one: Gary Gilmore, in 1977, who wanted to be executed.

You can see what happened to the murder rate. For several years ending in 1963 there were an average of just under 9000 murders per year, and a murder rate around 5 per 100,000. But, starting in 1964, as capital punishment was phased out, the murder rate started creeping upward.

The murder rate peaked at 23,040 (10.2 per 100,000) in 1980. But then the United States resumed executing a few murderers:

2 in 1979, 0 in 1980, 1 in 1981, 2 in 1982, 5 in 1983, 21 in 1984. (Over the last 20 years, the U.S. has averaged about 57 executions per year, all of them murderers.)

As the United States resumed executions, the murder rate began falling.

From the murder rate's peak of 10.2 per 100,000 in 1980, by 1984 (when executions of murderers were in the national news every few weeks) the murder rate had fallen to 7.9 per 100,000, a 22.5% drop. Despite the country's growing population, there were 4350 fewer murders in 1984 than there were in 1980.

But what I find most persuasive is how the murder rate compared to the overall violent crime rate. The overall violent crime rate came down too, but only slightly, and number of aggravated assaults actually went up slightly. In 1980, murders were 1.714% of all violent crimes. But in 1984, when executions of murderers were being reported on the news every few weeks, murders accounted for only 1.468% of all violent crimes. The overall violent crime rate decrease over that period can explain less than 1/3 of the drop in the murder rate.

Many factors can affect the overall violent crime rate, including murders. Those factors include demographic shifts (e.g., as the baby boomers aged), community policing reforms (Ruben Greenberg, Bratton/Giuliani, etc.), punishment approaches and prison sentence lengths, the ebbs and flows of the illegal drug trade, etc. But only one of those factors stands out as being something which could reasonably be expected to disproportionately affect the rate of capital crimes: capital punishment.

Based on those numbers, my best estimate is that the resumption of capital punishment for murder prevented about 3100 murders in 1984, a year in which there were 21 executions of murderers. That's more than 100 lives saved per executed murderer.

And that's why I changed my mind about the execution of murderers.

Moreover, there's a second line of evidence for the same conclusion, which is just as compelling. When you look at those execution and crime statistics, at the above links, there's another crime you should look at. There's a crime which used to be often punished by execution, but for which executions were phased out in the 1960s, and have not been resumed. That crime is rape.

In 1960, when the USA still executed both murderers and rapists, there were 1.89 rapes for every murder.

Now we execute people only for murder, never for rape. In 2013 there were 5.62 rapes for every murder.

The legal definition of rape has changed slightly over that half-century. Notably, there was no such thing as spousal rape in 1960, under the law. The 1962 MPC stated, “A male who has sexual intercourse with a female not his wife is guilty of rape if...” But spousal rape cases are still a small percentage of the total number of reported rape cases (reading between the lines of activists' literature, I'd guess 1%). So that couldn't account for the tripling of the reported rape/murder ratio. It seems likely that much of the change is due to the fact that rape ceased to be a capital crime, and murder did not.

Given these statistics, who can doubt the deterrent effect of capital punishment?

BTW, you shouldn't expect linearity of relationship between executions and deterred murders, because, in engineering terms, the information feedback mechanism isn't linear. In this case there was sizable “derivative feedback” because the press gives more extensive coverage to things which are novel.

The surge in executions 30-35 years ago got heavy press coverage, because of its novelty. It was the change in execution frequency (derivative), not just the execution frequency itself (proportional), which was responsible for the heavy press coverage. That heavy coverage caused an accelerated increase in the public awareness of the possibility of execution as a consequence of murder, and the murder rate promptly dropped by several thousand per year.

But you shouldn't expect that the second 2-3 dozen executions would have as great an effect as the first 2-3 dozen executions, because the novelty was wearing off, so the amount of press coverage for each execution was decreasing.

Derivative feedback classically results in an increase in the responsiveness of the system, beyond simple linearity. The fact that the first few dozen

executions resulted in a more dramatic effect than the continuation of that approximate rate of executions in subsequent years is a reflection of that. The feedback of

executions, through press coverage, to the inhibitory effect of fear of execution on potential murders constitutes a natural feedback control system, with proportional and

derivative components. It is not unlike intentionally designed PD (proportional/derivative) and PID (proportional/integral/derivative) control systems which are widely

used in industrial engineering, and studied in systems science:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?

Postscript: Economists Hashem Dezhbakhsh and Joanna M. Shepherd did a

far more detailed examination

of crime and execution statistics, including State-by-State analyses, and

reached the same conclusion. See: Dezhbakhsh, Hashem and Shepherd, Joanna,

The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: Evidence from a “Judicial Experiment” (July 2006).

Economic Inquiry, Vol. 44, Issue 3, pp. 512-535, 2006.

doi:10.1093/ei/cbj032.

This is “figure 1” from their paper:

See also: StamSummaryofDeathPenaltyStudies.pdf

# # #